Iron deficiency affects about 30 percent of the global population, making it one of the most common nutritional deficiencies in the world. It’s also one of the most harmful.

Consequences vary from impaired brain development in children and increased dementia risks in adults to a crippled immune system across all age groups.

Although children and pregnant women regularly get tested for anemia—a condition of not having enough red blood cells—doctors don’t usually screen adults for iron deficiency. And the condition can initially be so mild that it goes unnoticed for months or even years.

Consequences of Iron Deficiency

Iron deficiency leads to anemia because iron is needed to make hemoglobin, a protein that gives red blood cells their color and transports oxygen throughout the body.

But that’s far from iron’s only function.

1. Neurogenerative Diseases

Energy production requires iron.

Inside almost every cell, mitochondria generate energy for all activity, from weightlifting to forming thoughts. This cellular energy is called adenosine triphosphate, or ATP.

Iron is a raw material of ATP; lack of it impairs ATP production, which can manifest in the form of neurodegenerative diseases.

Parkinson’s Disease

Low iron levels can lead to reduced energy production in neurons. This energy deficit can contribute to the dysfunction and eventual death of dopamine-producing neurons, potentially exacerbating the progression of Parkinson’s disease.

One study found that low iron levels were associated with disease severity in Parkinson’s patients, while another showed an association between early-life anemia and the later development of Parkinson’s disease.

Dementia

“Iron is essential for proper brain development and function,” Dr. Matt Angove, a licensed naturopathic physician, told The Epoch Times.

Anemia is a risk factor for dementia, according to a 2020 study of more than 26,000 participants. The research suggests that iron supplementation reduces dementia risk in iron-deficient anemia patients. A 2023 study reaffirmed that iron deficiency is associated with greater all-cause dementia risk in women.

“These findings are unsurprising, knowing that iron plays critical roles in neurotransmitter synthesis and maintenance of myelin,” Dr. Angove said.

Layers of protein and fat called myelin sheaths protect brain and spinal cord nerves. Demyelination, damage or reduction of those sheaths, causes multiple sclerosis. A Journal of Clinical Investigation study found iron can repair demyelinating lesions.

2. Chronic Fatigue

A 2020 study in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition found associations between fatigue and iron deficiency in 224 hospitalized patients between the ages of 65 and 95. The study also reported that 11 percent of community dwellers and more than 50 percent of nursing home residents and inpatients were iron deficient.

Because oxygen relies on iron for transport, iron-deficiency anemia causes fatigue and poor muscle function. Even iron deficiency without anemia can cause extreme fatigue, highlighting iron’s vital roles.

3. Compromised Immune System

As iron is critical for the circulatory and nervous systems, research shows that it also helps maintain a robust immune system.

Iron supports innate and adaptive immune responses against foreign invaders. For example, low iron is associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes.

People with COVID-19 were found to have less iron in their blood and more substances such as ferritin, a protein that stores iron, than healthy people. Even two months after getting COVID-19, these patients still showed low iron and high ferritin levels.

“Ferritin is an acute phase reactant. High ferritin is a sign of inflammation,” Dr. Angove said.

During an infection, the body “pulls iron out of circulation and hides it in ferritin so viruses can’t utilize it.”

Who’s Most at Risk of Iron Deficiency?

Although anyone may develop iron deficiency without sufficient dietary iron, three groups are disproportionately affected: children, women, and older adults.

Children

In children, rapid growth causes deficiency, which impairs cognitive, motor, socioemotional, and neurophysiological development short- and long-term, according to research. It also has the potential to cause permanent damage to brain development.

Women

Menstruating women are also at high risk since they lose iron monthly because of bleeding. A study of 236 menstruating women found that 27 percent were anemic and that 60 percent were severely iron deficient.

Iron deficiency is common in active women, according to Dr. Angove. He described the case of a 17-year-old volleyball player whose arm went numb mid-game. Physicians suspected autoimmunity, but her ferritin was just two ng/mL, far below the optimum of 40 to 300 ng/mL.

“We started her on iron, and a week later, she was playing in the state volleyball tournament,” Dr. Angove said.

Her complete blood count was normal, so doctors didn’t suspect deficiency issues.

“She could have easily been down the road of specialist after specialist and ended up getting told she has a mental illness if we didn’t check her ferritin and get her iron levels up,” Dr. Angove said. “A patient’s need is often so simplistic that it confounds brilliant physicians.”

Pregnant women are also at a much higher risk of iron deficiency because of increased blood volume, fetal development needs, placenta formation, and maternal tissue growth.

How to Spot Silent Iron Deficiency

From irritability to headaches, signs of the condition can be wide-ranging, according to Dr. Angove.

Hence, they’re often overlooked.

The most common sign is fatigue, but others include:

- Pale skin

- Weakness

- Shortness of breath

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Cold hands and feet

- Brittle nails

- Pica (craving nonfood items)

- Restless legs syndrome

- Irritability

- Poor concentration

When checking for iron deficiency, Dr. Angove recommends including tests for ferritin, serum iron, total iron binding capacity, iron saturation, and complete blood count.

How to Optimize Iron Levels

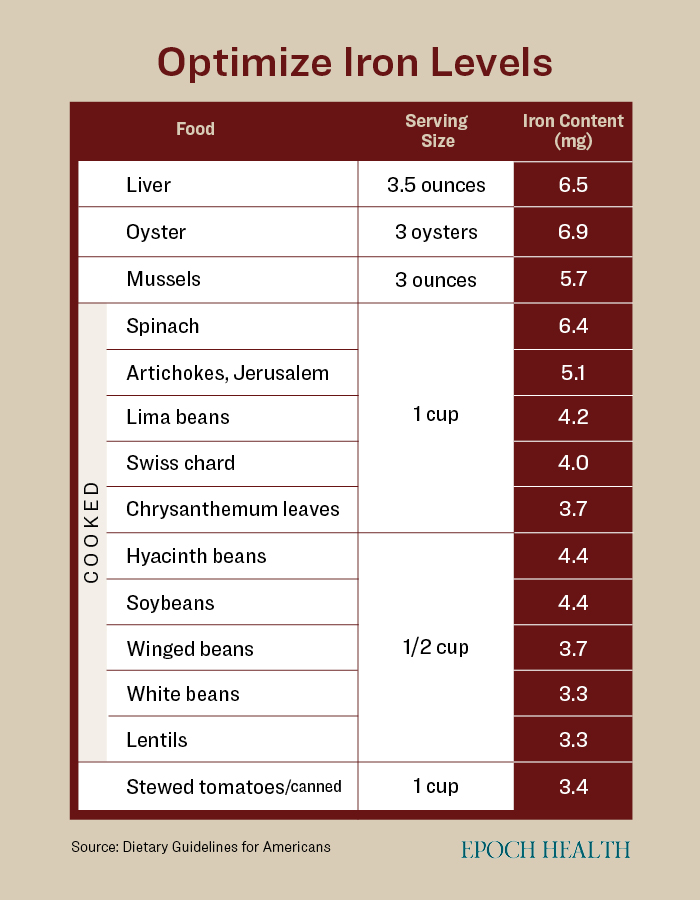

There are two dietary iron types: heme iron, in animal products such as meat, seafood, and poultry, and nonheme iron, in plant foods such as beans, greens, and fortified grains.

“While we absorb the heme iron found in animal products more efficiently, we can increase our absorption of nonheme iron by pairing it with a source of vitamin C, such as citrus fruits, strawberries, kiwi, or bell peppers,” registered dietitian Laura Kauffman told The Epoch Times.

Iron supplementation is often recommended for deficiency (ferritin under 25 ng/mL) and during pregnancy but can cause gastrointestinal issues such as abdominal pain and constipation. To avoid them, Dr. Angove recommends hydrolyzed whole protein chelate iron supplements.

Eating more foods rich in iron is also an option.