A new class of cancer drug in development shrank the tumors in six of 12 advanced cancer patients in a clinical trial, without causing severe side effects seen with previous versions of this class of drugs, according to a recent report.

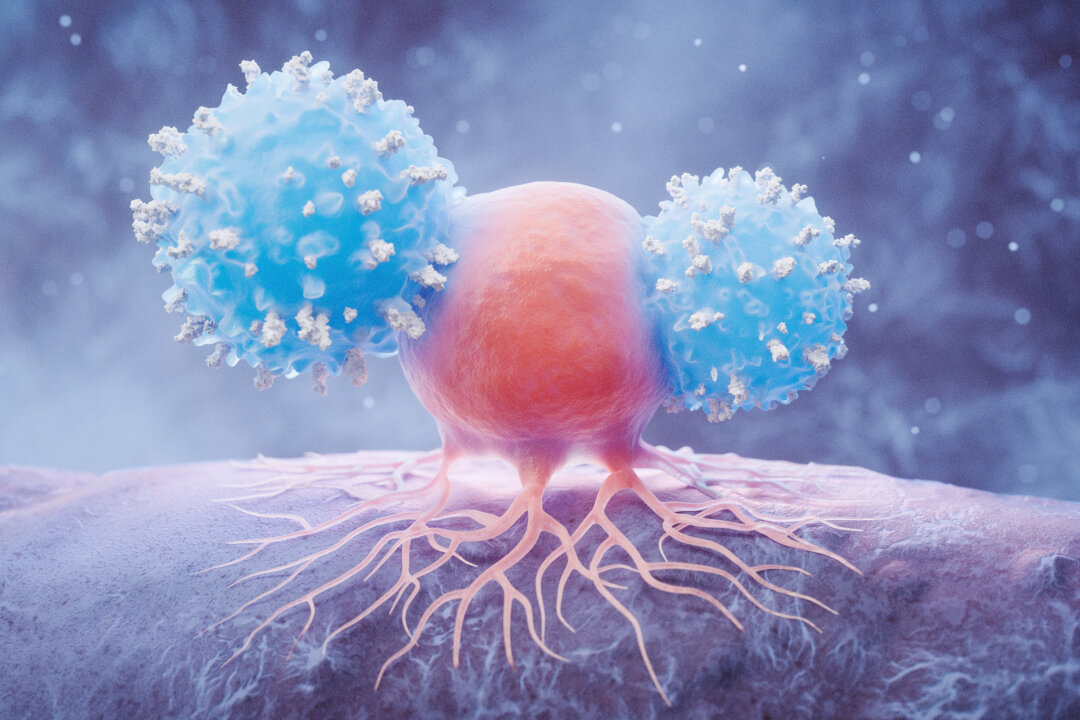

The treatment uses CD40 agonist antibodies, a type of immunotherapy that uses the body’s immune system to attack cancer.

Although this drug class has shown promise for two decades, development has been hampered by severe side effects, including widespread inflammation, low blood platelet counts, and liver toxicity—even at low doses.

Systemic Response From Local Treatment

The trial included 12 patients with various advanced cancers, including melanoma, kidney cancer, and breast cancer. Six patients experienced tumor shrinkage, and in two of those cases, the tumors disappeared completely.

The drug’s effects were not limited to tumors that were directly injected with the drug; cancer tumors elsewhere in the body also shrank or were completely destroyed.

“Seeing these significant shrinkages and even complete remission in such a small subset of patients is quite remarkable,” Dr. Juan Osorio—lead author of the study, visiting assistant professor at Rockefeller University, and a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center—said.

One melanoma patient had dozens of tumors on her leg and foot, but after multiple injections into just one tumor, all other tumors vanished. The breast cancer patient had tumors in her skin, liver, and lung that all disappeared following injection of a single skin tumor.

“This effect—where you inject locally but see a systemic response—that’s not something seen very often in any clinical treatment,” study author Dr. Jeffrey V. Ravetch, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Genetics and Immunology at Rockefeller University, said. “It’s another very dramatic and unexpected result from our trial.”

None of the 12 patients experienced the severe side effects typical of previous CD40 therapies.

Tissue analysis confirmed that the drug stimulated immune activity within the tumors.

CD40 is a protein found on immune cells that, when activated, prompts the immune system to fight tumors and develop tumor-specific T cells. The trial used an enhanced version of the CD40 antibody drug that engages a specific receptor on immune cells called Fc receptors, amplifying the immune response.

“We were quite surprised to see that the tumors became full of immune cells—including different types of dendritic cells, T cells, and mature B cells—that formed aggregates resembling something like a lymph node,” Osorio said, emphasizing that these structures are associated with better treatment outcomes.

Addressing Treatment-Resistant Cancers

Dr. John Oertle, chief medical officer and cancer specialist at Envita Medical Centers, who was not involved in the study, told The Epoch Times that this approach could help treat cancers currently resistant to existing immunotherapies.

He said many resistant cancers exhibit “immune exhaustion,” in which T cells become dysfunctional and unable to mount an effective attack against cancer despite their presence.

Injecting the CD40 agonist directly into a tumor may help “reprogram” the tumor microenvironment, restore immune vitality, and drive T cell infiltration to break through treatment resistance, he said.

“However, this is rarely a one-size-fits-all solution,” he said. “Designing combinations that are tailored to the patient’s specific disease biology and immune profile is critical to sustaining responses and improving overall outcomes.”

Severe Side Effects Had Slowed Development

Developing CD40 antibodies for cancer treatment has taken more than 20 years of research.

While animal trials showed these drugs to be effective in clearing cancer, human trials found that they also caused widespread inflammation, low blood platelet counts, and liver toxicity, even at low doses.

However, in 2018, researchers at Rockefeller University’s Laboratory of Molecular Genetics and Immunology made a key breakthrough. Led by Ravetch, the team engineered an enhanced version of the CD40 antibody, 2141-V11, to boost immune system activation while minimizing harmful side effects.

The modified drug binds more tightly to CD40 receptors on human cells and is 10 times more potent at activating anticancer immune responses. Rather than administering the drug through traditional intravenous infusion, which often caused toxicity because of widespread CD40 receptors on healthy cells, in the recent clinical trial, published in October, researchers switched to injecting the drug directly into tumors.

Next Steps and Broader Impact

These findings have led to additional clinical trials in collaboration with Memorial Sloan Kettering and Duke University, which are currently in their early phases. These studies are exploring 2141-V11’s effects on cancers such as bladder, prostate, and glioblastoma, an aggressive and deadly brain cancer. Nearly 200 patients are enrolled.

Researchers seek to understand why some patients respond to the drug while others do not. For example, the two patients whose cancers disappeared had high levels of T cells, immune cells that kill cancer cells, before treatment.

“This suggests there are some requirements from the immune system in order for this drug to work, and we’re in the process of dissecting these characteristics in more granular detail in these larger studies,” Ravetch said.

He noted a broader challenge in cancer immunotherapy: Only 25 percent to 30 percent of patients will respond to immunotherapy, so the biggest challenge in the field is to try to determine which patients will benefit from it.

Oertle said, “While this trial is early and the patient number is small, the fact that we’re seeing complete remissions in aggressive cancers from localized injection is a very encouraging sign.”