The refusal of the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the suit of Texas and 17 other states against four states (Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) that were alleged not to have conducted fair presidential elections, on the grounds of Texas’s lack of standing, is a grievous abdication.

The claim of Texas and the other states was that failing to protect against fraudulent voting on a large scale that affected the results for each state, and cumulatively between the defendant states to affect the outcome of the election of the president and vice president, was a violation of Texas’s right to an adequate level of assurance that the constitutional process of selection of the president and vice president was truly followed.

The attorney general of Pennsylvania called the Texas lawsuit a “seditious” attempt to disenfranchise the people of his state, and the Trump-hating media gave it the usual total-immersion in reflexive mockery.

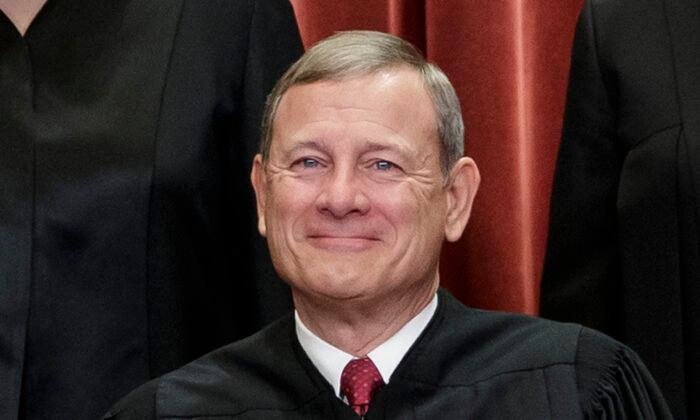

Official processes aren’t more important than the election of the president; no right is more fundamental than the assurance of the constitutional selection of the president. The Supreme Court’s decision can only be seen as another illustration of its determination under notoriously controversy-averse Chief Justice John Roberts to avoid any judgment that might produce a partisan backlash.

This appeared to have been the case in determining that Obamacare was a tax (which is nonsense). It’s one thing to hear a case and produce a dubious motivation for a decision, but something else to decline to hear a case in a matter not of appellate but of original Supreme Court jurisdiction—a dispute between states—on the fatuous theory that the 18 complainant states have no right to a high comfort level that the people elevated to the national offices have, in fact, been constitutionally elected.

Criminalization of Policy Differences

If the Supreme Court and lower courts won’t exercise their full responsibility, the judiciary ceases to be a coequal branch of the government, the Constitution cannot function, and the political direction of the country is determined in an increasingly lawless contest between political factions in the executive and legislative branches, with no determining regard to the legality of their conduct.The role of the judiciary is then demoted to being fought over for the criminalization of policy differences—it then ceases to be just a matter of legislating, but of driving the opponent from office after a partisan conviction of “high crimes,” a term that can be redefined to suit the occasion.

I was one of those (and we were not numerous) who urged the chief justice at the end of the farcical impeachment trial of President Donald Trump in February to inveigh about the inadvisability of frivolous and vexatious attempts to remove high officeholders.

I was also one of those who warned the extremely small readership I then had nearly 50 years ago during the Watergate controversy, of the dangers of criminalizing policy differences in the U.S. government.

But that process has become addictive and almost reflexive. No conclusive evidence has ever come to light that President Richard Nixon committed any crimes, although some members of his entourage undoubtedly did. And he didn’t discourage an ambience in the inner circles of the White House that tolerated a casual attitude toward taking liberties in the interests of national security.

The charges against President Bill Clinton were never adequately grave to justify an impeachment trial.

There was no conclusive evidence that Trump did what he was accused of doing in his impeachment case—abuse of power and obstruction of Congress, and neither is an impeachable offense (any president who wouldn’t obstruct this Congress is guilty of negligence).

The first presidential impeachment trial, of Andrew Johnson in 1868, was also preposterous—the president fired a Cabinet official, for cause.

It would have been entirely appropriate and very useful if at the end of the Trump impeachment process, the chief justice had stated, in recording the verdict of the Senate, that frivolous and vexatious harassments of presidents and other high officials for partisan reasons aren’t in the country’s interest.

A Two-Legged Stool

Something ultimately will have to be done to end this meretricious and destructive process of trying to mobilize partisan legislators to convict political opponents of crimes. But unless the judiciary fulfills its constitutional status as a coequal branch of government, it’s to this depth of squalid bloodless assassination that U.S. government will be reduced.It’s now a country with a totalitarian, left-of-center press, and a judiciary that is politically biased by or intimidated by the left, where, because of the pusillanimity of the Supreme Court, it’s now the law that elections may be rigged with no oversight, except within the state where the rigging occurred.

With a bench that is incapacitated in the most politically important matters, Madison’s magnificent triumvirate of equal branches of government will degenerate into a two-legged stool, in which the president will be a virtual dictator when his party controls the Congress, and he will be constantly vulnerable to harassment and threat of almost capricious removal when his opponents control the Congress.

The judiciary would then be reduced essentially to arbitrate the immense mass of civil litigation that afflicts and throttles daily and commercial life in the United States, and to be a rubber stamp for the prosecutocracy that enjoys a 98 percent conviction rate, more than 95 percent of it without trial, in the continuous demonstration of the abuses of the plea-bargain rules that permit prosecutors to extort and suborn perjury at no legal risk to themselves or the untruthful witnesses (who receive immunity from accusations of perjury).

Such a country, with a stunted judiciary, will shortly fall into a state of institutional decrepitude where its highest courts no longer have the moral authority to bring down judgments on the political leaders even if they had the will to do so. It would be a severely hamstrung parliamentary system in which the executive can only serve at the pleasure of legislative majorities and minority governments are dismissed from office as criminals.

This may all seem a bit remote, but when the Supreme Court creates a vacuum by abdicating as it did last week, the vacuum created doesn’t cozily await the return of justice; the vacuum will be filled by the power-accretive politicians in the legislative and executive branches and there will be no one to mediate or arbitrate between them.

The judiciary’s task is to assure that the Constitution is upheld. If it doesn’t play that role, the Constitution won’t be upheld. The United States could ultimately replicate Rome, where 22 of the 30 emperors elevated between Tiberius and Diocletian died violently. Presumably, there have been, in these 17 centuries of intervening decadence, enough refinement of political thought and practice, that hasty departures from the presidency won’t be violent.

If the deterioration of the quality of the media, the courts, the elections, the candidates, and at least superficially, of the cultural standards of the people also, is not temporary, the consequences will ultimately destroy the American republic (confirming Benjamin Franklin’s famous premonition). The United States will be at the edge of a precipice, with all of Western civilization precariously attached to it.

Friends Read Free